Iranian artiste Makan Ashgvari’s experiments with sound and words

Artist interview with Makan Ashgvari for The Telegraph t2 by Anannya Sarkar. Read the full article online here

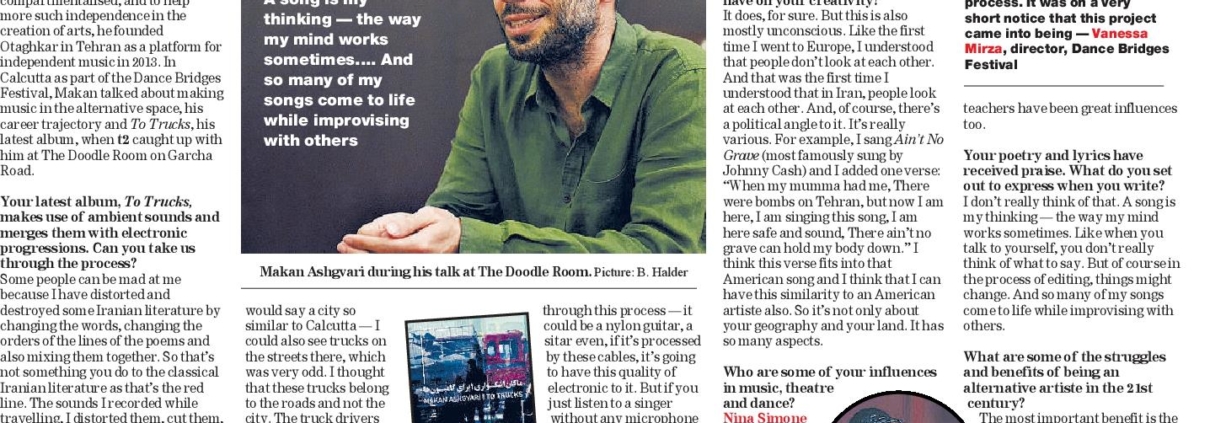

As an electronic musician, Makan Ashgvari likes to weave his surroundings into his creative work, like the sound of trucks lumbering on the roads of Tehran where he lives. As an artiste, Makan refuses to be compartmentalised, and to help more such independence in the creation of arts, he founded Otaghkar in Tehran as a platform for independent music in 2013. In Calcutta as part of the Dance Bridges Festival, Makan talked about making music in the alternative space, his career trajectory and To Trucks, his latest album, when t2 caught up with him at The Doodle Room on Garcha Road.

Your latest album, To Trucks, makes use of ambient sounds and merges them with electronic progressions. Can you take us through the process?

Some people can be mad at me because I have distorted and destroyed some Iranian literature by changing the words, changing the orders of the lines of the poems and also mixing them together. So that’s not something you do to the classical Iranian literature as that’s the red line. The sounds I recorded while travelling, I distorted them, cut them, re-recorded them and transformed them. The sounds that I recorded while travelling are called Side A and I call the poems and songs that I borrowed from classical literature and transformed, Side B. So Side A is a geographic journey and Side B is a journey in time and I looked at my album as a tape, like you can play the other side. I hitchhiked a lot in Iran and while travelling I was seeing so many trucks on the road and even when I was back in Tehran — I would say a city so similar to Calcutta — I could also see trucks on the streets there, which was very odd. I thought that these trucks belong to the roads and not the city. The truck drivers treat the truck as a live person — for example, if you offer biscuits to a live person, they will say that the truck will be upset as the truck is like the host.

To the uninitiated, how would you explain what electronic music is?

I would say if you listen to a fluorescent, there is a noise, a sound; if you listen to a lamp, there is a sound. So for me the sound that goes through this process — it could be a nylon guitar, a sitar even, if it’s processed by these cables, it’s going to have this quality of electronic to it. But if you just listen to a singer without any microphone or speakers, that is acoustic music.

If you see MTV Unplugged, it’s a band you know, like Nirvana or Florence and the Machine, and they use acoustic instruments, still that has an electronic side to it as it’s going through amplifiers, cables and speakers. I don’t identify my music as electronic, you know. I think nowadays if you’re not listening to a sitar player in a room without a microphone and speakers, I think that’s the only acoustic music that exists. If it goes through a wire, it’s electronic.

Given that you are based out of Iran, what impact does the state have on your creativity?

It does, for sure. But this is also mostly unconscious. Like the first time I went to Europe, I understood that people don’t look at each other. And that was the first time I understood that in Iran, people look at each other. And, of course, there’s a political angle to it. It’s really various. For example, I sang Ain’t No Grave (most famously sung by Johnny Cash) and I added one verse: “When my mumma had me, There were bombs on Tehran, but now I am here, I am singing this song, I am here safe and sound, There ain’t no grave can hold my body down.” I think this verse fits into that American song and I think that I can have this similarity to an American artiste also. So it’s not only about your geography and your land. It has so many aspects.

Who are some of your influences in music, theatre and dance?

Nina Simone is definitely an influence —her diversity and her personality as someone who cares about what’s going on in the world. Also, Farhad, the Iranian singer. John Cage is an artiste with no limits and whose works I have performed. All my teachers have been great influences too.

Your poetry and lyrics have received praise. What do you set out to express when you write?

I don’t really think of that. A song is my thinking — the way my mind works sometimes. Like when you talk to yourself, you don’t really think of what to say. But of course in the process of editing, things might change. And so many of my songs come to life while improvising with others.

What are some of the struggles and benefits of being an alternative artiste in the 21st century?

The most important benefit is the Internet, which I think by mistake we musicians see as a thread, because sometimes we believe that every single product should be sold directly to the audience. We have to acknowledge the power of the Internet and appreciate it as a tool. The struggle is that of being focused. So many options, tools and facilities can confuse you sometimes.

“I think the audience enjoyed Makan’s innovative sound, visual presentation and the stories behind his creative process. It was on a very short notice that this project came into being” — Vanessa Mirza, director, Dance Bridges Festival

You can view the highlights of the artist talk here

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!